Our History

From Past To Present

There is sparse evidence of any sort of settlement in the Wokingham area prior to the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons: a few Neolithic tools, a possible flattened Bronze Age barrow, a Roman cremation burial.

This is not really surprising, since Wokingham is and always has been forest land. In the early years of Saxon settlement, the followers of a man called Wocca, who had made their home at Woking in Surrey, set out across the Berkshire Moors in search of new lands to settle. They cleared themselves some land on the edge of the forest and so began “Wocca’s People’s Home” or Wokingham. Some of them even went a little further and stopped at Wokefield in Stratfield Mortimer. For a long period through the 17th to the 19th centuries, Wokingham was known as Oakingham, but this was a corruption that has now been dispensed with.

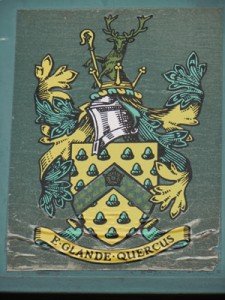

Oakingham means the “town of the forest” and this is where the acorns on the coat of arms are derived. It is also reflected in the town motto E Glande Quercus meaning “from the acorn, the oak.” In 1953 the former Borough of Wokingham was granted the Arms and in 1975 the Queen authorised that they could be used by the Wokingham Town Council. The Arms consist of a field of acorns on a gold shield representing Wokingham as a forest town, an ermine chevron, a Tudor rose and a Saxon crown representing the Saxon origin of the district. There is also a stag supporting a bishop´s crozier which refers to the Bishop of Salisbury who owned the land until 1574, when it became a Royal town.

Wokingham does not appear in the Domesday Survey of 1086. The first actual mention of the place in extant records comes in 1146 when Sonning, with Dunsden and Wokingham” is recorded amongst lands owned by the Bishop of Salisbury. These Bishops, originally Bishops of Sonning, had had a residence at the first village since the early 10th century. The special reference to Dunsden and Wokingham may indicate that they were the only other villages in the large minster-parish with their own chapels. The names of Wokingham chaplains are known from around 1160 and what is now the parish church was certainly standing by 1190 when Bishop Hubert Walter (later Archbishop of Canterbury) visited and dedicated the building to All Saints. It still retains small parts of this Norman chapel today. Wokingham Chapel had the right of baptism and burial, so the villagers did not have to make the long trek to Sonning.

Because half of Wokingham was owned by the Bishop of Salisbury, that section, including Ashridge Manor, was always officially a detached part of the county of Wiltshire and not in Berkshire at all. At the corner of Rose (Rows) Street and Wiltshire Road can be seen a post that reminds us of this peculiar situation that gained the latter road its name. It used to stand in Cross Street, and marked the boundary between the two counties until 1845, when all of Wokingham fell to Berkshire and the outer parts were divided off as the parish of Wokingham Without. There were a number of other hamlets around the village that have now been swallowed up as suburbs of Wokingham: Toutley Common (Emmbrook), Matthewsgreen, Dowlesgreen, Froghall Green, Chapel Green (Luckley), and East Heath. Rural manors which can still be recognised in places of today include Evendon’s, Norreys’, Woodcray, Buckhurst (St. Anne’s Manor) and Beche’s. The latter was the home of the original Palmers, the De La Beches (not apparently related to the family of the same name from Aldworth), after whom both the manor and Peach Street are named, and the Whitelockes, whose sons included the prominent Edmund and Bulstrode Whitelocke. The manor house survived as a fine 1624 mansion until it burnt down in 1953. It was then an hotel. The dower house of the same estate is now the Holt School. Cantley (Natthewsgreen House), Glebelands and Luckley (home of the Palmers) were other important estates. Two of these Victorian houses are by Edward Newton. Luckley has moved from its original site which sat half-way between the present Luckley and Ludgrove Houses.

By 1219, Bishop Richard Poore decided to found a ‘new town’ at Wokingham in order to boost his income. He was about to start work on building the present Salisbury Cathedral and so, no doubt, was in sore need of the funds. He extended the village sited around the chapel, having burgage plots laid out along two parallel streets heading south-west (Peach and Rose Street) to a triangular market place (where the town hall now stands). He then gained permission to hold a market in there every Tuesday. Forty years later rights to hold a fair on St. Barnabas’ Day and All Saints’ Day were added. Broad Street and Denmark (Down) Street were established shortly afterwards and the market moved into the former’s wide avenue. The scheme seems to have worked well and Wokingham grew into a thriving medieval centre for Windsor Forest folk, full of commerce and industry. Wokingham became particularly noted for its Bell Foundry. As early as 1383 the industry was well established in the town, and many local churches ring out on Wokingham Bells. Only Bell Foundry Lane now remains where the owner’s held a farm. The foundry itself was in the centre of the town, but, by the late 16th century, it had relocated to Reading. There are still many interesting and historic buildings in Wokingham dating back to medieval times. In Rose Street are a remarkable series of medieval ‘Wealden’ (Sussex-style) hall houses, some of which date back to the late 14th century. One of these you can even visit, as it’s currently the ‘Metropolitan’ public house. A slightly later house in the same street was the childhood home of chimney-sweep, James Seward, in the 1850s. He eventually became the inspiration for ‘Tom’ in Charles Kingsley’s The Water Babies. A sculpture outside the library remembers him. The 15th century Overhangs, in Peach Street, were once the Windsor Forest Verderers’ Court. Here were heard cases of offences committed within the bounds of the Royal Forest. The judges could extract fines for minor offences, but more serious cases had to be referred elsewhere.

Queen Elizabeth I is said to have visited Wokingham a number of times, whilst riding out from Easthampstead Park and taking the healing waters at the Gorrick Well in the woods at Luckley. Inside the parish church, there is a fine and rare Royal Arms of her reign (1582) featuring the Welsh Dragon in place of the Scottish Unicorn. Not far away is a memorial to local man, Thomas Godwin, whose preaching skills had encouraged the lady to make him Bishop of Bath & Wells in 1584. Archbishop William Laud’s parents also lived in Rose Street a few years before his birth. In 1583, Queen Elizabeth granted Wokingham its first Charter, although it did not finally rid itself of the Steward of Sonning’s influence until James I granted a more wide-ranging version in 1612. Fines and court profits now went to the town, rather than Sonning Manor. Wokingham instituted an ‘Alderman’ (mayor), nineteen burgesses and a high steward, and erected a fine guildhall with many pillared ground floor (see picture above), which was unfortunately demolished in 1858. The best surviving 16th century building in the town, the Tudor House looking directly down Broad Street with its superb timber-framed facade, but this part is not original. It was brought from the ruinous Billingbear Park in the 1920s. At about the time of Elizabeth’s charter, Flemish weavers fleeing from religious persecution made Wokingham famous for its manufacture of silken goods. The industry flourished, dominating the town until the early 19th century, when trade declined due to cheap French imports. The townspeople turned to alternatives. The market became famous for its ‘fatted fowls’ which were bought for resale in London. Then there was leatherworking, wool-dealing, brick-making, brewing and coach-building. The Lush Brothers made coaches for King Edward VII, Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein and Empress Eugenie of the French.

During the Civil War, Wokingham was mostly a Roundhead town. At one stage, the Royalist garrison from Reading arrived in the town, demanding the townspeople fill eight carts full with firewood and bedding. When they refused, the troops burnt four town houses to the ground. The occupiers were told to take themselves off to parliament-supporting Windsor. Much of the local gentry, however, was Royalist in its sympathies. Tales of woe brought on by the Civil War, are recounted on a most extraordinary block of Portland stone at the entrance to the parish churchyard. This monument to the wife and nephew of one Benjamin Beaver (1761) gives a complete family history including the story of how a Beaver ancestor, along with his brother-in-law, Richard Harrison, were almost ruined raising three troops of horse for the King at their own expense. By the time of the restoration, about twenty percent of the town had been destroyed in the upheaval. This, despite the fact that the commander-in-chief of the Berkshire troops was himself a Wokingham man. Major-General Sir Richard ‘Moses’ Browne grew up in the town. He was the man who led Charles II’s triumphant procession into London at the Restoration. Not many years afterwards, things were looking up for the town and it benefited from a number of bequests. Richard Palmer in 1664, provided for a curfew bell at the church to be rung at 4am and 8pm between September and March. This was so strangers lost in the countryside could know the time and receive some guidance as to the right way to go. The following year, Wokingham’s famous ‘Lucas Hospital’ was founded by the estate of Henry Lucas, secretary to the Earl of Holland – who had no other connection with the town, but an interest in the people of Windsor Forest. These almshouses are said to be Wokingham’s finest building.

At heart, Wopkingham remained a rough tough kind of place. Cock fighting was popular and there was once a famous cock-pit at the end of Cock Pit Path. This was also the scene of female wrestling, where topless ‘ladies’ fought until one dropped the penny that they each held in one hand. There was also a big prize-fight in the town in 1787, when Tom Johnson beat Bill Warr for the title of Champion of England. However, the place was best known for its bull baiting. Having been once mauled by a bull, in 1661, a local butcher, named George Staverton, left the rent from his house to provide such a creature for the townsfolk to bait in the Market Place every St. Thomas’ Day. This horrible ‘sport’continued in the town until banned by the Corporation in 1821. Despite the nation following suit six years later, the last bull baiting in England took place here in 1832. The bull was still provided as beef for the poor, but before the unfortunate creature could be slaughtered, an excited mob seized the animal and set the dogs upon it, as of old. People came from miles around to see the spectacle, and the vast crowds often got quite rough. In 1794, Elizabeth North was found dead after the baiting, and the parish register also records:

Martha May, aged 55,

who was hurt by fighters after the Bull-baiting,

was buried December 31st, 1808.

Wokingham’s unsavoury forest reputation was further enhanced by the criminals who frequented the town, and, by 1675, the authorities were forced to build a lock-up there. The gallant French highwayman, Claude Duval, worked this area and is said to have owned a cottage in Highwater Lane at that time. More thieves appeared in the following century. In 1723, a white paper was passed in Parliament, making it a criminal offence to undertake blacking, the painting of one’s face black in order to commit unlawful acts. It was know as the Black Act and was so called after the infamous Wokingham Blacks, a band of footpads who infested Windsor Forest. They began as mere poachers, but soon expanded their list of nefarious activities to encompass such crimes as robbery, blackmail and even murder. Their little base at one William Shorter’s house in Wokingham soon commanded nearly all criminal activity in Eastern Berkshire. The locals were afraid to speak out against them, for retaliation was swift and merciless. Even the local magistrates were not safe. Eventually, the custodian of Bigshotte Rayle (Ravenswood) called in the Bow Street Runners to entrap the leading miscreants. Two disguised officers arrived and made friends with three of the Blacks at Wokingham Fair. They convinced them that there was plenty of easy money to be had by becoming professional witnesses in London. Meeting some days later, in a Holborn tavern, the unsuspecting Berkshire lads were quickly taken into custody. Their arrest led to a major round up and the gang was broken.

Wokingham does not show much evidence of the great profits of the 18th century being turned into fine town houses. Although Broad Street does feature the superb ‘Elms,’ a dower house built around an older building for the Pitts of Swallowfield Park around 1730 and Montague House of 1820 built on the site of an earlier school. The magnificent Baptist Church was first built in 1774 (rebuilt 1861). So there were more genteel people frequenting the town. Businesses must have benefiting, however, from establishment, in 1759, of the Turnpike Road from Reading to Sunninghill, and thence to London. William Heelas arrived at Buckhurst sometime in the 1790s and set up business as a linen draper in the town. Over the centuries the shop expanded to cover most of the north side of the Market Place. Heelas are no longer in the town but their second branch has, of course, become Reading’s greatest Department Store, now owned by John Lewis. One of the old Wokingham buildings is now part of Boots. It was during this period that Wokingham’s pubs and inns came into their own. The Duke of Wellington frequented the Rose Inn in the 1820s, on his way to Stratfield Saye; but a hundred years earlier it was already famous as the residence of the much celebrated barmaid, Fair Molly Mogg. She was the publican’s daughter who had been brought to public attention through a ballad written for her by Pope, Gay, Swift and Arbuthnot. Being a local man, Alexander Pope often visited the inn and, finding himself stranded there, one day, during a violent storm, he and his friends set about to extol the virtues of their beautiful hostess. The obsessive suitor, mentioned in the rhyme, was said to have been the young Lord of Arborfield whose advances she rejected. Although some claim this was her sister, Sally, who was even more beautiful. Furthermore, the Rose was not that which we see today, but an older building which stood on the site of the present Boots. Though nationally not as well known as Molly Mogg, Molly Millar is better known locally for the Lane which bears her name. Who this lady was, however, is something of a mystery. One theory says the lane was named by the Welsh Drovers who passed this way with their sheep in the late 18th century and got to know Molly, an old woman who lived by the wayside. Local legend says more: she was not just any old lady but the town witch!

The Railway arrived in Wokingham in 1849 and the following two decades were a great time of civic pride and much public building work. The present town hall, including a police court and prison, was erected in 1858, and Henry Woodyer’s St. Paul’s Church for John Walter of Bearwood in 1864. This all culminated in the creation of the Borough Council in 1885 and the replacement of the Alderman (the last one in the country) with a mayor; and, since, the town is proud to have risen to the top of the list of the nation’s most favoured places to live.

Thanks to David Nash Ford’s Royal Berkshire History